Current smart manufacturing technologies face significant challenges, particularly in ensuring the health status of equipment within smart factories.

Take CNC machine tools as an example.When failures occur or machining accuracy declines, timely detection and intervention are essential.

If operators fail to identify and address these issues promptly, scrap rates increase significantly.

In addition, critical machine components may suffer damage.This damage can ultimately lead to substantial losses in factory productivity.

Therefore, establishing a comprehensive equipment health monitoring system to perform health checks after startup and before machining has become crucial for ensuring stable and reliable smart manufacturing processes.

The types of data that can characterize CNC machine health are diverse.

COCCA et al. analyzed voltage and current signals during CNC milling machine operation.

Their objective was to prevent costly catastrophic failures and production interruptions.

This approach also helps extend the service life of CNC equipment.

YUAN et al. developed dual-temperature and threshold models based on permissible temperature rise for motors and bearings to monitor electric spindle health.

Huang Hua et al. utilized vibration signals during CNC machine operation to precisely pinpoint failure causes, enabling accurate identification of unknown feed system faults.

The selection and design of evaluation methods significantly impact the accuracy of assessment results.

WANC et al. proposed a method based on multi-domain analysis and convolutional neural networks for effective spindle health assessment;

Chi et al. proposed a method combining graph theory algorithms and ant colony optimization support vector machines for rapid and precise machine tool fault diagnosis;

Zhu et al. integrated heterogeneous fault information extracted from multiple sensors.

They used a multi-branch Bayesian neural network for this purpose.

The network was built on deep convolutional neural networks and multilayer perceptrons.

This approach enhanced the accuracy of machine tool health monitoring.

It also improved the robustness of the monitoring system.

While these studies represent significant progress in health evaluation algorithms, limitations remain in detection time and economic costs.

For instance, real-world workshop operations do not involve simultaneous startup/shutdown of all machines, and health inspection frequency requirements vary.

Moreover, most existing CNC machine fault prediction and health management research relies on optimal sensor layouts and neglects machining costs—a critical factor in production guidance within factory environments.

To address these challenges, this study developed a CNC machine health detection technology based on self-evaluation.

This technology supports both group and individual detection, is low-cost, sensor-independent, and adaptable to user scenarios.

Engineers developed an edge-computing software system for deployment on shop floor industrial computers.They validated the system through experiments.

The entire detection process takes only 3 minutes, achieving 96.9% accuracy while significantly reducing labor and material costs.

Health Self-Check Solution

A well-designed self-check solution is essential for achieving precise assessment of key components in CNC machine tools.

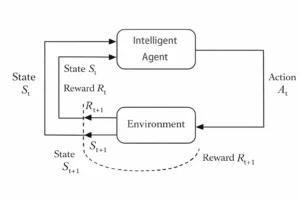

The overall solution, as shown in Figure 1, primarily encompasses NC program design, signal acquisition, intelligent diagnostic evaluation models, and validation applications.

The specific steps include several key aspects.

First, engineers design customized NC self-check programs tailored to the no-load operating conditions of the target equipment.

Next, they identify and confirm suitable signal types for data acquisition.

They then employ data collection techniques based on industrial communication protocols.

Engineers combine these techniques with PLC sensorless signal extraction methods.

This approach enables the capture of state characteristics of critical components.

Such components include the spindle system and feed mechanisms.

Finally, engineers establish a CNC machine health evaluation model.They base this model on sensorless signal acquisition.

They achieve this by performing correlation analysis between vibration signal features and expert field assessments.

Based on this model, designing a CNC machine health self-diagnostic software system and conducting experimental validation in a multi-machine workshop environment to assess software feasibility and evaluation accuracy.

NC Program Design

During the startup and operation of CNC machine tools, the warm-up phase plays a crucial role in enhancing machining accuracy, reducing wear, and extending service life.

Most self-diagnostic products on the market currently operate independently.They do not relate to actual workpiece machining.

Furthermore, conventional self-diagnostic procedures scheduled before workpiece machining can impact CNC machine tool longevity, consume actual machining time during processing, and impose additional workload demands on operators.

Therefore, this paper proposes integrating CNC machine health self-checks into the warm-up process.

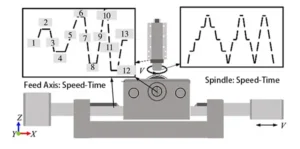

The spindle, a critical component that drives cutting tools or workpieces to remove excess material, primarily functions to support and transmit power and torque.

Typically, spindle motion undergoes a sequence of transitions: from stationary to low-speed rotation, high-speed machining, post-machining completion, and finally to a stopped state.

Moreover, during high-speed operation within the spindle, the absence of a tool clamping mechanism can easily cause screw loosening, potentially damaging the spindle bearings.

The feed system employs two fundamental motion modes during operation: linear feed and rotary machining.

Conventional CNC machine tools rely on the coordinated action of three linear feed axes—X, Y, and Z—to remove material from the workpiece at varying feed rates, including both high and low speeds.

Similar to the spindle, the feed system also possesses stepless speed regulation capability.

In summary, designing a health self-check NC program requires a comprehensive evaluation approach.

Engineers must calculate the CNC machine’s health evaluation grade.

They do so by considering the machine’s warm-up program.They also account for spindle tool clamping conditions.

In addition, they evaluate the health status of the spindle system at different speeds.

They assess the condition of the feed system across varying operating speeds as well.

Therefore, the overall motion plan for the CNC machine tool, as shown in Figure 2, is as follows:

Spindle and feed axes warm up at low speed; Spindle clamps the tool; Spindle speed changes in a stepwise manner;

Feed axes operate at low, medium, and high speeds throughout the entire process; the program stops.

Selection of Machine Tool Health Self-Check Signals

Multi-source signals such as temperature, vibration, current, and rotational speed are commonly used as raw data for assessing the health status of CNC machine tools.

However, for most CNC machine tools, vibration signals are difficult to acquire using sensorless methods like PLCs, message queues (e.g., Kafka), or TCP/IP.

Utilizing vibration data requires the additional installation of external sensors, which inevitably increases the cost of health self-checks.

During the brief execution of the self-check program, the temperature of a CNC machine tool typically does not undergo significant changes.

Therefore, engineers can aggregate and analyze multiple sensorless data points obtained through CNC system communications.

These data points reflect dynamic information that changes with machining status.

Such information includes parameters like rotational speed and current.Engineers can select these dynamic parameters as research signals.

They use these signals to evaluate the health status of the CNC machine tool’s feed system.

Engineers must record the CNC machine tool’s current program name, current program line number, and current time.

This ensures accurate data collection and facilitates data categorization.Table 1 lists the signal types required for self-diagnosis.

| Fusion Method | Computational Complexity | Real-Time Performance | Anti-Interference Capability | Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kalman Filtering | Medium | High | Medium | Parameter State Estimation |

| Bayesian Inference | High | Medium | High | Fault Diagnosis |

| Deep Fusion Network | Very High | Low | Very High | Complex State Recognition |

| D-S Evidence Theory | Medium | Medium | High | Uncertainty Handling |

Neural Network-Based Health Evaluation Model for CNC Machine Tools

As the core component of a machine tool health monitoring system, the evaluation model’s construction process constitutes a systematic engineering endeavor, primarily encompassing four key steps:

First, raw operational data is acquired through vibration sensors and a multi-source data acquisition system.

Second, the collected raw data undergoes preprocessing, including data cleaning, noise reduction, outlier removal, and data normalization.

Third, engineers perform feature extraction using time-frequency analysis and Pearson correlation coefficients.

Finally, they construct a health status assessment model using a BP neural network based on the extracted feature parameters.

This model enables accurate evaluation and prediction of the machine tool’s health status.

In practical applications of CNC machine tool health self-diagnosis methods, operators do not use vibration sensors during actual operation.

They use vibration sensors only during the model establishment stage.

At this stage, engineers determine the health status classification of the self-diagnosis model.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

When employing data-driven machine learning methods to evaluate the health status of CNC machine tool feed systems, it is essential to accurately collect data representing healthy, suboptimal, and faulty system conditions to train the model.

This ensures the machine has sufficient raw data for self-learning. In data mining projects, data preprocessing accounts for over 70% of the total work time.

The accuracy of data input directly determines the model’s reliability and generalization capability.

1. Sensorless Fault Data Acquisition

In actual production machining, most CNC machines operate in healthy working conditions, making it difficult to obtain data on non-healthy states.

To address this, we simulate a linear degradation trend from healthy to sub-healthy to faulty states by adjusting the gain parameters of the AC servo control system and the spindle control parameters.

Taking the feed axis speed loop gain as an example, we apply the concept of control variables for analysis.

All parameters are set to optimal values, representing the machine tool’s healthy operating state.

Increasing the speed loop gain heightens the feed system’s sensitivity to speed changes, accelerating speed response but causing greater speed fluctuations in the feed axis.

This induces overshoot and oscillation phenomena, thereby simulating the healthy state of the CNC machine tool’s feed system across different periods.

Huang Wei validated the applicability of this method in his research on CNC machine tool health status based on the random forest algorithm.

As shown in Table 2, engineers incrementally adjusted the feed system and spindle control parameters of the CNC machine tool during data acquisition.

They designated the four machine tool states as a, b, c, and d, representing healthy, good, passable, and faulty, respectively.

Under identical conditions, each group underwent three experiments.

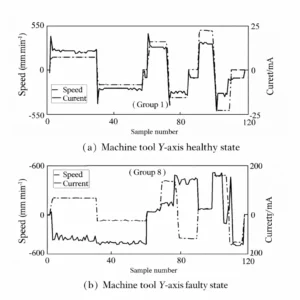

Groups 1–4: CNC machines operated in healthy and good working conditions, with stable servo speed and current output, and minimal vibration amplitude.

Group 5: Mild whining occurred on the X-axis at certain positions. Noise levels increased during Y-axis feed, Z-axis feed, and spindle rotation, accompanied by slight bed vibration.

Health status downgraded to good.Groups 6 and 7 exhibited continuous whining along the entire X-axis travel.

Y-axis, Z-axis, and spindle loads became extremely unstable, with increased machine body vibration, resulting in a Passable health rating.

Group 8 produced persistent whining during all servo axis movements, accompanied by a sharp screech from the spindle and severe machine vibration, leading to a Faulty health rating.

While analyzing actual spindle speed, linear axis feed rate, and current signals under different conditions as evaluation algorithm data sources, vibration sensors captured corresponding linear feed axis vibration data.

The system displayed this data in real time on-site, giving experts more intuitive vibration metrics to support their evaluations.

This approach minimized errors from subjectivity and randomness in subsequent validation experiments, enhancing the reliability of evaluation results.

| Experiment No. | A: Data Acquisition Frequency / Hz | B: Feature Extraction Algorithm | C: Parameter Optimization Strategy | D: Control Response Time / ms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | Wavelet Transform | Genetic Algorithm | 50 |

| 2 | 100 | Deep Learning | Reinforcement Learning | 25 |

| 3 | 100 | Principal Component Analysis | Gradient Descent | 10 |

| 4 | 500 | Wavelet Transform | Reinforcement Learning | 10 |

| 5 | 500 | Deep Learning | Gradient Descent | 50 |

| 6 | 500 | Principal Component Analysis | Genetic Algorithm | 25 |

| 7 | 1000 | Wavelet Transform | Gradient Descent | 25 |

| 8 | 1000 | Deep Learning | Genetic Algorithm | 10 |

| 9 | 1000 | Principal Component Analysis | Reinforcement Learning | 50 |

2. Vibration Data Acquisition

Using the LC5104A-50 vibration sensor, vibration signals are collected from the near-end of the X, Y, and Z feed axes and the spindle during the CNC machine tool’s health self-check program, with a sampling frequency of 1000Hz.

Operators must continuously acquire speed signals, current signals, and vibration data without changing the sensor positions.

This ensures the synchrony and accuracy of the collected data.

On-site experts then promptly analyze this data to determine the CNC machine tool’s health evaluation grade under the current parameters.

Data Analysis and Feature Extraction

Data collected through communication with the CNC system enables assessment of the machine tool’s health status.

Taking the Y-axis servo system as an example, Figure 3 shows the speed and current curves captured under healthy (Group 1) and faulty (Group 8) conditions.

Comparison reveals that during healthy operation, the CNC machine exhibits relatively stable current and speed values, smaller current peaks, and smoother vibration characteristics.

In contrast, during fault conditions, the current and speed curves become unstable, current peaks increase significantly, and vibration intensifies markedly.

Whether it be the spindle or the servo system, both rely on the motor of the CNC machine tool to drive the execution of various machining operations.

The power expression for the motor is:

-1-300x49.png)

According to Newton’s second and third laws, Fzu represents the resistive forces acting on the motion of each component, while Fdj denotes the driving force generated by the motor’s output torque:

-1-300x73.png)

Functional component power consumption:

-1-300x72.png)

Assuming the motor power consumption equals the feed axis power consumption and the motor power consumption equals the spindle power consumption, respectively, we obtain:

-1-300x61.png)

The acceleration of the spindle and feed axes occurs over an extremely short time interval, and in most cases, each axis moves at a constant velocity.

As t approaches zero, we can consider this acceleration negligible.

The spindle and feed axes’ I²/v ratio is positively correlated with the motor’s output power and torque.

Damage to the spindle bearings, wear on the lead screw, or motor failure will all increase the CNC machine tool motor’s output torque and power, resulting in a larger I²/v ratio.

Using the Y-axis servo system as an example again, Figure 4 shows the current-speed relationship curves (i.e., I²/v curves) during self-diagnostic phases when the CNC machine tool is in healthy and faulty states.

Each curve stage corresponds directly to the stages in Figure 3.

Odd-numbered stages represent acceleration/deceleration changes on the Y-axis, while even-numbered stages indicate uniform motion.

Comparison reveals that during machine tool malfunctions, acceleration/deceleration curves become indistinguishable from uniform motion curves, and the uniform motion curves exhibit instability.

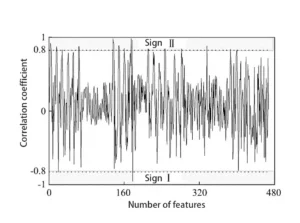

The Pearson correlation coefficient measures the linear relationship between two variables X and Y.

It is generally denoted as r(X,Y) and expressed mathematically as:

-300x65.png)

In the equation: X represents the feature vector, Y represents the label vector, indicating the health status of CNC machine tools;

Cov(X,Y) denotes the covariance between X and Y, while Var|X|Var|Y| represents the product of the variances of X and Y.

The Pearson correlation coefficient ranges from -1 to 1.

The closer the value of r(X,Y) approaches ±1, the stronger the linear correlation between the two variables; conversely, the weaker the correlation.

In this paper, the feature vectors are time-domain features and dynamic response coefficients.

Feature extraction is performed for each stage of the spindle and servo system, including the mean x, variance S², standard deviation σ, root mean square (rms), mean square value (msv), k, s, bxz, fzz, mcz, ydz, and other time-domain features.

Dynamic response parameters include the rise time tr, peak time tpσ%, settling time ts, overshoot σ%, oscillation count N, and peak values peak from the current curve.

The main spindle has 273 features, while the servo axis has 194 features. In this paper, these features are treated as vector X.

Based on expert experience and vibration signals, a reasonable evaluation score for the current health status of the CNC machine tool is used as vector Y for model training.

We determine the correlation coefficient between the extracted feature values and the CNC machine tool’s health status by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient.

The calculation results are shown in Figure 5.

Model Construction

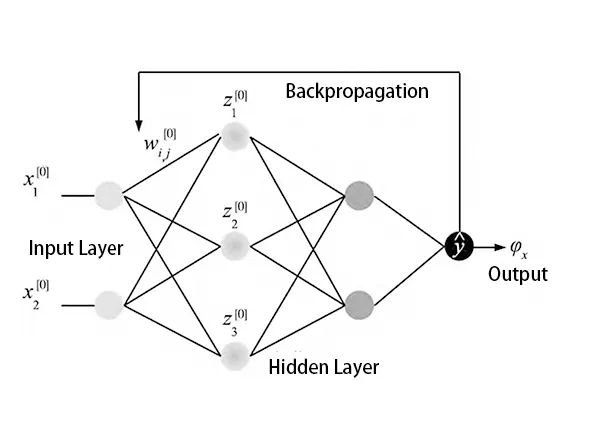

The core of the BP (backpropagation) neural network relies on error backpropagation to correct parameters in multilayer feedforward networks.

It is one of the most widely applied artificial neural network models, comprising a feedforward pathway consisting of input layers, output layers, and hidden layers.

As shown in Figure 6, each circle represents a neuron. Neurons in the input layer receive raw data inputs from external sources.

Within the model’s hidden layer, the model adjusts parameters such as input weights and bias values, which handle the spatial transformation and feature extraction of input data.

Depending on the complexity of input information, the hidden layer can be single-layer or multi-layer.

The final layer of neurons forms the output layer, synthesizing all neural information to complete a forward propagation cycle within the feedforward network.

When the actual output φx deviates significantly from the desired output beyond a predetermined range, the model enters the backpropagation phase.

Through methods like gradient descent, the network adjusts the weights and biases within the feedforward network.

This iterative process continues until the loss function meets the specified criteria, thereby completing the construction of the network model.

The forward propagation formula for the BP neural network is:

-300x63.png)

In the formula: X = [X1, X2, …, Xn]T represents the input, denoting all extracted features characterizing the machine tool’s health status;

W = [W1, W2, …, Wn]T denotes the weights; b is the bias;

f is the activation function, where the Sigmoid function is employed to normalize the probability output between 0 and 1.

.png)

Compute the loss function using the output of a single forward pass through the network and the actual labels:

-300x90.png)

Using gradient descent, iterate through errors to find the optimal bias and weight coefficients:

-300x82.png)

Forward computation and backpropagation continue iteratively until Ek satisfies the stopping condition.

The network’s final output φx represents the current health status.

Selecting the BP neural network model to evaluate results by identifying nonlinear relationships between selected feature values and CNC machine health status yields not a precise mathematical value but a classification interval.

To determine more accurate, specific mathematical values for CNC machine health status, we must perform further calculations beyond neural network classification:

-300x61.png)

In the formula, x represents the boundary value of the classification interval, x denotes the classification interval, yi is the i-th feature value with a correlation coefficient absolute value greater than 0.8 in feature selection, ri is the Pearson coefficient corresponding to the feature value.

When φx is ab, c, and d respectively, x is 90, 70, and 30. β is 20 and 30. The final health status evaluation result for CNC machine tool components is calculated using f(x).

The overall evaluation of the CNC machine tool is the minimum value among all component evaluations.

Development of a Machine Tool Health Self-Diagnostic System

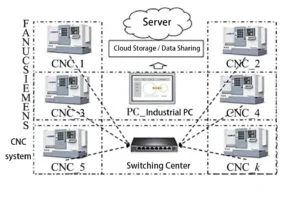

In smart workshop monitoring and management, IoT technology is widely applied to fulfill intelligent requirements such as information exchange between personnel and equipment, inter-device communication, condition control, and data storage.

As shown in Figure 7, this illustrates the data transmission flow for health self-check information within a CNC machine tool cluster under IoT technology.

Here, CNC_1 to CNC_K represent all three-axis CNC machine tools that can participate in health self-checks within a specific smart workshop.

These machine tools include those equipped with mainstream domestic and international CNC systems.

Examples include FANUC, SIEMENS, Mitsubishi, HNC, and KOD systems.

Different CNC systems do not share unified data acquisition methods.They also lack standardized function interfaces.

Therefore, engineers select appropriate data communication protocols based on the specific CNC system and machine environment.

These protocols include TCP/IP communication. They also include Modbus serial communication and OPC UA.

After an operator at the edge device clicks and confirms the startup self-check, the server automatically transmits the generated NC program to the CNC machine.

After the CNC machine begins operation, data collected from each machine is uniformly forwarded to a fixed MAC address via a switch.

The PC serves as the fixed terminal, primarily performing calculations on collected data, visualization processing, local storage, and data cloud services.

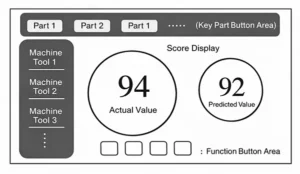

The software system was developed using Qt Creator 5.0, with the main interface layout shown in Figure 8.

The self-check interface displays key component scores, buttons for critical CNC machine tool components, the names of machines participating in the inspection, and logical function buttons for the software.

When a CNC machine participates in inspection for the first time, necessary configurations must be made on this interface. Subsequent inspections can proceed directly.

Clicking the corresponding function buttons allows viewing the current inspection progress for all CNC machines, component score radar charts, and historical score change curves for individual areas and the entire CNC machine.

Experimental Validation

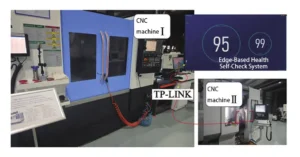

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed machine tool health self-diagnosis method, this study constructed the experimental platform shown in Figure 9.

The platform primarily consists of the following components:

① CNC Machine Tool I: A three-axis vertical machining center equipped with a FANUC system;

CNC Machine Tool II: A vertical turning-milling composite machine equipped with a SIEMENS CNC system;

② Data Acquisition System: An 8-port Gigabit TP-LINK switch;

③ Host computer: Equipped with an Intel Core i7-10700 processor, 16GB RAM, and running Windows 10 operating system.

Machine tools are uniformly connected to the TP-LINK switch via network cables.

The designed CNC machine tool health self-check system is deployed on the workshop’s host computer.

With operator assistance, dedicated self-check NC programs are developed based on the hardware specifications of both machines.

These programs solely control machine operation and do not include modifications to CNC system servo parameters.

Changes to CNC system parameters require manual command input.

During the no-load operation of the CNC machine tool, the program runs as follows:

After the machine tool warms up, the spindle clamps the tool and performs rapid vertical movements at speeds of 3000, 6000, and 8000.

The X, Y, and Z axes then traverse their full travel ranges at feed rates of 180, 375, and 500 respectively.

Single-run inspection results indicate that CNC Machine II is in good health status. CNC Machine I’s Z-axis received a score of 76, indicating poor health status.

Analysis of the current, speed, and speed-current characteristics generated by the Z-axis during program execution is shown in Figure 10.

The Z-axis remained stationary in the stable image segment. During this period, the system monitored the status of other components.

The Z-axis exhibited slight velocity fluctuations at multiple points, accompanied by unstable current readings.

Simultaneously, the I2/v image displayed extreme values, indicating a sudden increase in resistance on the CNC machine tool’s axis motor.

This signaled that the Z-axis was in an unhealthy state.

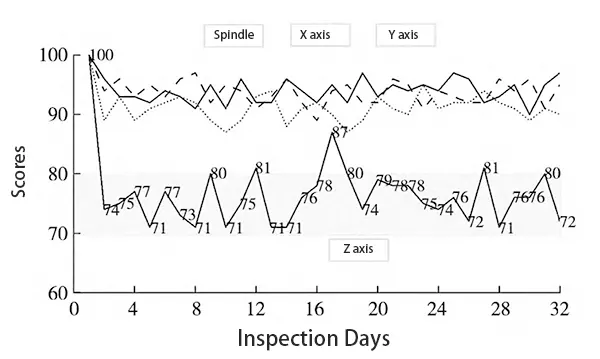

To validate the model’s long-term stability and accuracy, daily startup inspections were conducted on CNC Machine Tool I for one month, with evaluation results recorded.

As shown in Figure 11, the experimental findings are as follows:

The X-axis and Y-axis remained in a healthy state throughout the long-term monitoring period, while the Z-axis was consistently in a sub-healthy state.

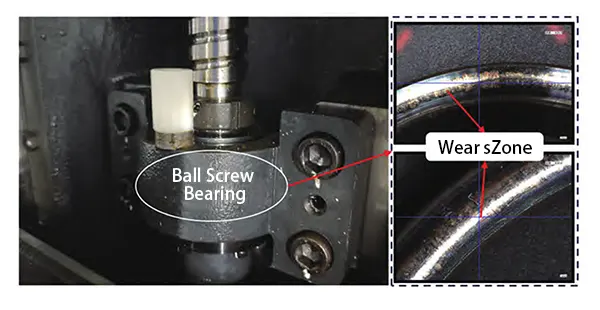

A comprehensive test was conducted on the Z-axis of CNC Machine Tool I for troubleshooting.

As shown in Figure 12, the long-term loading test revealed repeated friction between the Z-axis ball bearings and the lead screw groove, resulting in the rupture of the lubricating oil film and reduced motion stability.

This explains why the overall evaluation of the CNC machine tool frequently showed a sub-healthy state due to the influence of the Z-axis.

The proposed model algorithm achieved an accuracy rate of 96.9%.

By altering the classification algorithms employed in the model, the following comparative experiments were conducted:

① K-means classification yielded an accuracy rate of 0.806;

② Naive Bayes model achieved an accuracy rate of 0.838;

③ Random Forest (RF) model attained an accuracy rate of 0.903.

The experiments used the evaluation of the Z-axis in machining centers under sub-optimal conditions as the source for accuracy rate calculations.

Given the characteristics of the collected experimental data—limited volume and simple structure—the model training time was measured in milliseconds and was not considered a factor in selecting the classification algorithm.

Therefore, the experimental results demonstrate that the BP neural network algorithm adopted in the proposed model significantly outperforms other classification methods.

Conclusion

Maintaining CNC machine tools in optimal operational condition not only significantly enhances production efficiency but also propels factories toward “unmanned” operations, serving as a crucial component of industrial intelligence.

This paper focuses on the health status of CNC machine tool feed systems.

Considering production efficiency and cost issues in industrial manufacturing, it proposes a sensorless self-diagnostic technology for CNC machine tool health monitoring.

(1) This sensorless approach addresses the high economic cost of existing CNC machine health self-diagnostic systems by reducing hardware expenses.

(2) It proposes analyzing current-velocity simulations of motor operation impedance to characterize machine health.

A health self-diagnostic model based on a BP neural network was designed, and a CNC machine health self-diagnostic system was developed to monitor the health status of the feed system.

The system incorporates radar charts displaying health intervals. Fault diagnosis recommendations are embedded in the software backend as an expert knowledge base.

After machine tool inspection, fault types and diagnostic suggestions are displayed in a text box.

Evaluation results closely match expert assessments, and the software system is already in use.

(3) The current model is limited to detecting issues during no-load operation after machine startup.

Therefore, future research will update the self-diagnostic model with an incremental learning framework, dynamically updating model parameters using online data.

A TinyML lightweight model will be designed to adapt to real-time computational resource constraints.